The fashion company collaborated with Brandalised, a company that does have a license to sell Banksy’s art, for the collection.

Banksy Encourages Fans to Steal From GUESS: “They’ve Helped Themselves to My Artwork Without Asking”

Carys Anderson

Book of living stories

The fashion company collaborated with Brandalised, a company that does have a license to sell Banksy’s art, for the collection.

Banksy Encourages Fans to Steal From GUESS: “They’ve Helped Themselves to My Artwork Without Asking”

Carys Anderson

Calabria, the southernmost region of the Italian peninsula, is the birthplace of some of the world’s most well-known myths, such as the terrifying tale of Scylla and Charybdis immortalized in the Odyssey. Yet one local curiosity remains in obscurity. Wander through the gardens of Calabrian churches or abandoned farmland in late autumn or early winter and you may glimpse it—a tree that appears to be strung with pearls. But this tree is no myth.

Archaeologist and native Calabrian Dr. Anna Maria Rotella first heard about the Olivo della Madonna, an ancient white-olive cultivar, in 2017, while working at an archaeological excavation site in Catanzaro. Due to their stunning appearance, locals have long called them the Olive Trees of the Madonna.

Despite growing up in olive-rich Calabria, Rotella had never seen such a tree, and her curiosity was piqued. While on-site, one of the workers told her unfortunate news from his hometown nearby: their last Olivo della Madonna had been lost to a fire. Hearing this, Rotella became determined to discover if other such trees still existed.

“I called everyone,” Rotella remembers. “I refused to accept that these trees had all disappeared.”

Calabrian landowners, olive-oil makers, and locals all told Rotella about where the trees once were, along with colorful and sometimes confusing stories. But eventually, she collected enough confirmed sightings to begin mapping the locations of the trees still standing.

Later that year, she saw an Olivo della Madonna for the first time. The tree was about 50 years old and adorned in abundant, resplendent white olives. “I understood then the sense of the sacred,” says Rotella. “Any Calabrian that has the fortune of encountering one does not see anything that appears different from the other olive trees for the whole year, then one day passes by again and they perceive the transformation.”

“No, not the transformation,” she muses, after a pause. “But the magic, the miracle of this thing that should be black, but instead becomes white.”

Rotella explains that, historically, many Calabrians have felt deeply connected to religious stories of survival. Such tales give them strength to get through the enormous hardships—from earthquakes to mafia corruption—that have afflicted them throughout the ages. Given this religiosity, the prodigio (an Italian word that can mean “miracle,” “marvel” or “wonder”) of a white-fruiting olive tree “could not be anything but sacred to our great-grandfathers and farmers,” says Rotella.

Exactly how many generations of Calabrians have beheld the Olivo della Madonna remains unclear. “There are no written texts because ours is an oral tradition,” says Rotella. But they have always been rare: Only a few living Calabrian elders have memories of the trees.

It is possible that the Olivo della Madonna has been growing in scattered spots throughout the Mediterranean for thousands of years. To date, Rotella has identified about 120 of these trees growing around Calabria, the oldest of which began to grow around three centuries ago.

The olives are only white when fresh. In brine, they darken like other olive varieties, which are green when unripe due to chlorophyll and later become black when fully ripe due to their anthocyanins. The pure white color of the Leucocarpa comes from a genetic lack of these pigments. Rotella plans to continue experimenting to preserve this particular characteristic in the olives beyond the harvest, but her primary focus is on the preservation of the trees themselves.

As recently as 50 years ago, the trees were cultivated in the vicinity of churches, which used oil from the olives to light their lamps before electricity reached rural Calabrian communities. The oil was often offered as a donation and may also have been used as a sacrament in blessings, baptisms, and other religious rituals.

But while Calabrians venerated the white olive, they rarely consumed it. Rotella has uncovered very few past or present instances of the oil or olives being used as a part of local cuisine, besides accounts from farmers of frying the olives and eating them as a frugal, simple snack while working. The oil from white olives is transparent and, according to Rotella, was generally considered too spicy and unusual for the Calabrian palate.

The white olive trees standing today face many challenges. Most are threatened by climate change, which has led to increasing instances of infestations of olive fruit flies, drought, extreme heat, and wildfires. Rotella is working to raise awareness to protect the oldest trees, while also growing new ones at specialty plant nurseries. Her work is driven by a personal sense of awe in the plant’s existence, but increased plantings may prove useful in supporting genetic diversity among Italian olive cultivars.

Securing funds to do so has proved difficult, but Rotella has found success returning to the Olivo della Madonna’s religious roots. Through collaboration with Calabrian churches over the past two years, she has planted trees front of at least 80 places of worship, increasing the known number of white olives in Calabria to more than 200. Now, she is looking to extend this initiative beyond Calabria, into Sicily and Northern Italy, as well as more broadly across the Mediterranean, with help from growers and organizations with an interest in preserving Italian culture and natural biodiversity in Europe.

Rotella remains hopeful that other white olive trees will be discovered beyond the 200 she knows of so far or has herself helped to plant. More trees may ensure that this sacred, living artifact will not become mere myth.

As we reach the end of another year, it’s time to look back at some of our favorite non-fiction articles from 2022! As you may have guessed from the title, this year we’ve decided to break with tradition and split the list into two halves. This first piece features some of our favorite articles about […]

Women who use ride-sharing services like Uber have begun leaving hair and their fingerprints inside the car as evidence, in case they’re attacked.

The post Women Are Sharing How They Intentionally Leave Hair And Fingerprints In Taxis As Evidence, And It’s An Eye-Opening Reality Check first appeared on Bored Panda.

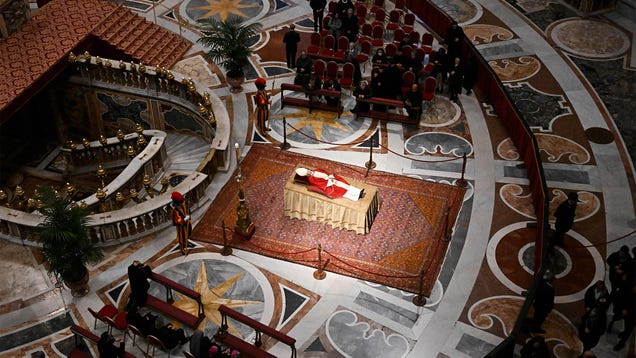

VATICAN CITY—In a requiem mass that followed strict liturgical protocol for a deceased head of the Roman Catholic Church, the funeral of Pope Benedict XVI reportedly concluded Thursday with the ritual eating of the former pontiff’s body. “Father, into your hands I commend his spirit, as we commend to our stomachs his…

While artificial intelligence (AI) models are becoming increasingly advanced, training and running these models on conventional computer hardware is very energy consuming. Engineers worldwide have thus been trying to create alternative, brain-inspired hardware that could better support the high computational load of AI systems.

The picturesque ruins of Beauly Priory in Beauly, Scotland, are home to Europe’s oldest Elm tree. Sadly, the tree is almost dead. The Wych Elm of Beauly Priory fell victim to Dutch elm disease, a virulent fungal infection spread by tiny bark beetles. In 2021, the tree was estimated to have less than five percent living material remaining.

This specimen of Ulmus glabra is estimated to be more than 800 years old. The priory was founded in the 1230s for an order of Valliscaulian monks. Priory records and deed documents from that time refer to the Elm already being there. Situated in a corner by the gate of the priory burying ground, the tree is also the last survivor of an avenue of Wych Elms appearing on an estate map from 1798-1800. The Beauly Elm has been recognized as a "Monumental Tree" and appears in the "Ancient Tree Inventory" of the Woodland Trust.

The tree has a startlingly surreal appearance—massive, gnarly, and heavily knotted with bare, tortured limbs extending haphazardly from its enormous trunk. With huge crown galls, whorls, and boles, its phantasmagoric appearance invokes images from both fairy tales and nightmares. The ravages of time and disease are readily apparent in its ancient, beleaguered form.

Wych (or Scots) Elm is the only Elm species native to the United Kingdom. Their hardiness makes them viable in the colder, harsher climate of the Scottish Highlands. In the 1960s, when Dutch Elm Disease arrived in southern England in a shipment of infected North American lumber, hope was that the same cooler and windier climate would protect Scotland’s Elms from the aggressive spread of the infection. The disease-carrying beetles are poor fliers and dislike the cold. Unfortunately, warmer temperatures beginning in 2018 facilitated the disease’s northward progression, and many of Scotland’s northernmost Elms have now succumbed.

Despite its demise, Historic Environment Scotland intends to maintain the Wych Elm of Beauly Priory in situ for as long as it is safe. Beloved by the town, the tree is a cultural, historical, and biological specimen that remains significant even in death.

View Signal Source

A bill in the Massachusetts state legislature, proposed by Democratic state Representatives Carlos González and Judith García, to create the Massachusetts Incarcerated Individual Bone Marrow and Organ Donation Program, which the legislation’s sponsors say “would restore bodily autonomy to incarcerated folks” and also…