A younger, slimmer, slightly-more-fearless ChefShwasty would tell you that this was solely out of boredom. The actual truth being is that at the age of 23, I discovered dark rums, and for a period of time, it made me fearless like a pirate. I felt like the world was at my fingertips.

revamped 1967 volkswagen bus becomes ‘back to the future’ time machine

the van features a ‘working’ flux capacitor (described by doc as ‘what makes time travel possible’) and an accurate recreation the time machine from the original film.

The post revamped 1967 volkswagen bus becomes ‘back to the future’ time machine appeared first on designboom | architecture & design magazine.

Jane Weaver – The Architect

Specific, and concentrated and acute, and whole

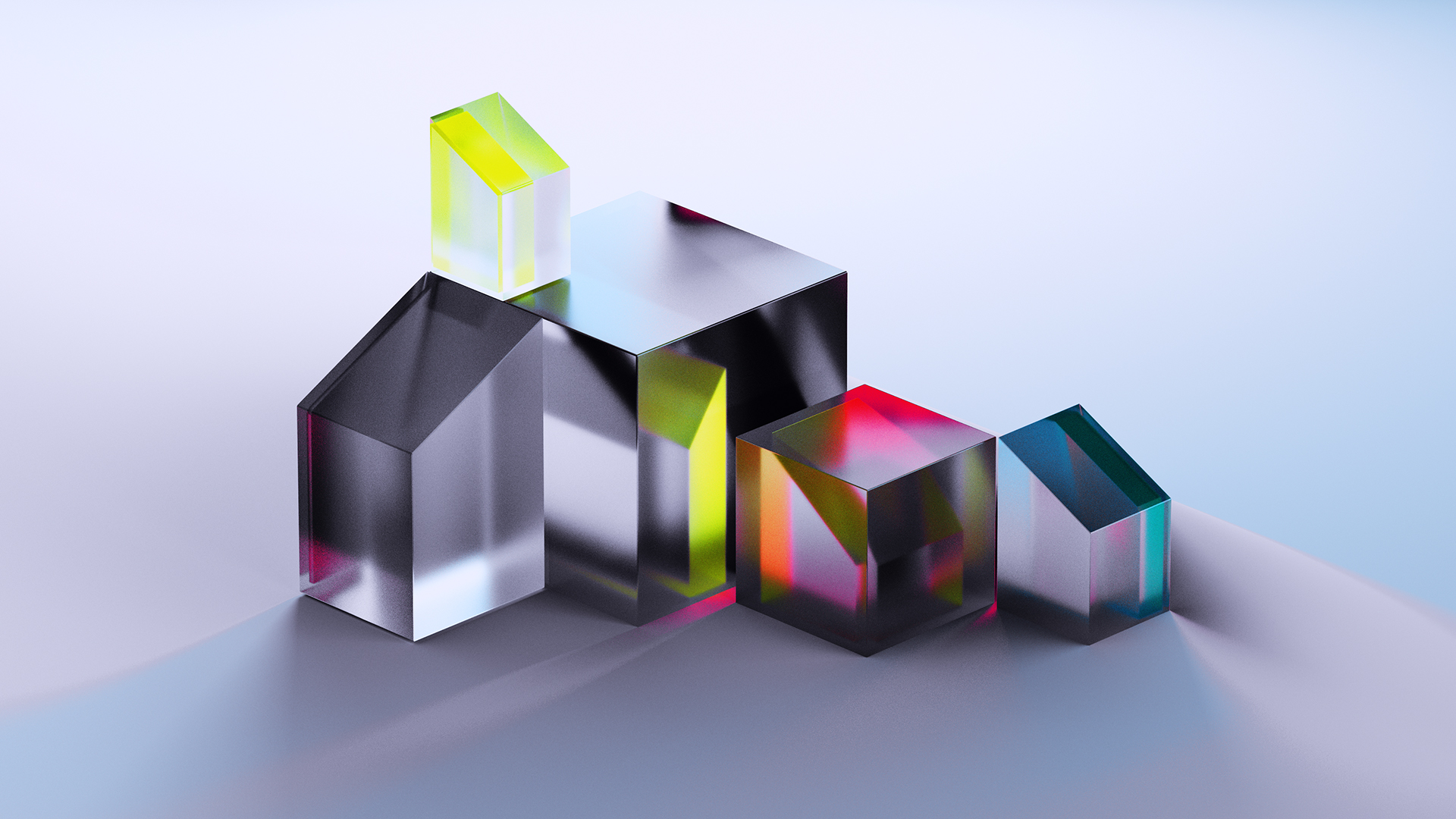

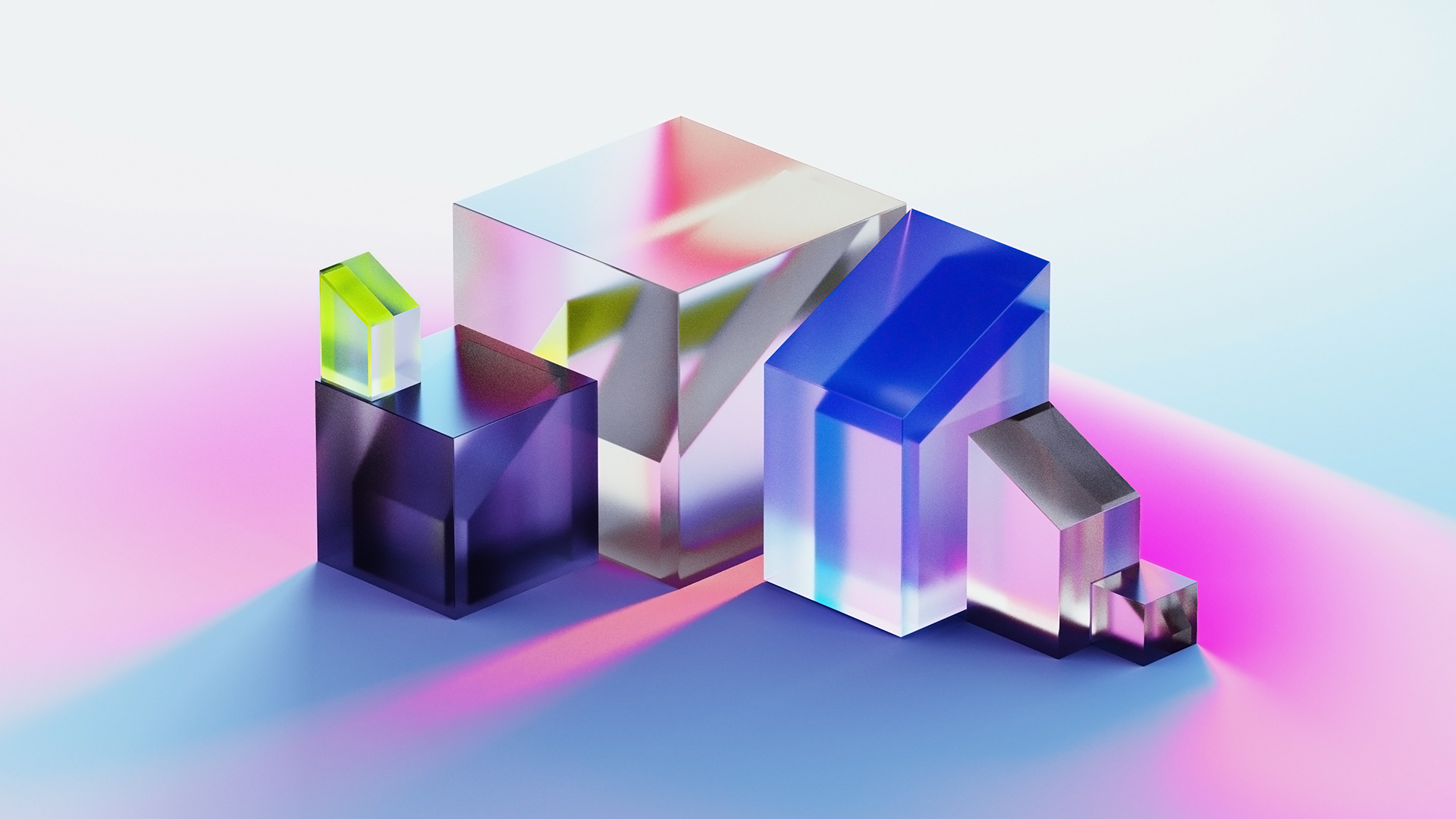

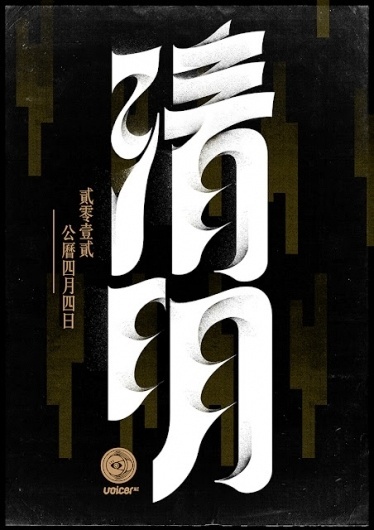

Daily Design Inspiration

Daily Design Inspiration

AoiroStudio

Nov 01, 2017

Part of the Daily Design Inspiration series that started it all on Abduzeedo. This is where you’ll find the most interesting things/finds/work curated by one of us to simply inspire your day. Furthermore, it’s an opportunity to feature work from more designers, photographers, and artists in general that we haven’t had the chance to write or feature about in the past.

For this Daily we are selecting in digital art, branding, editorial and more. Our goal is to diversify the types of work and in the future we can perhaps categorize them in different sections. For now we are going to stick to the simple format of images and links. I hope you enjoy and share with use via Twitter or our Tumblr.

Until further notice, we’ll display the images and the titles added to them. Because of little issues we had in the past, the images are still linked to their authors, we just won’t mentioned who shared them like we used to.

Daily Design Inspiration

The Luminescent Underwater Slug Pirates of the Mediterranean Sea

Sicilian sea slugs are ferocious hunters. Their prey of choice? Spiky hydroids, and lots of them. Each sea slug, or nudibranch, can snack on as many as 500 of the much smaller predators a day. All this hunting can presumably get pretty tiring, but scientists at the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom, have found that nudibranchs are careful to maximize their meals. They prefer, the scientists observed, to hunt hydroids that have recently had a meal of their own, like pirates claiming the booty of their prey.

"Effectively we have a sea slug living near the bottom of the ocean that is using another species as a fishing rod to provide access to plankton that it otherwise wouldn’t have," marine ecologist Trevor Willis, lead author of the paper in Biology Letters, said in a statement.

Hydroids, distant cousins to coral, feed on tiny plankton and other small crustaceans. Scientists offered sea slugs a variety of dining options: plankton, hungry hydroids, and hydroids that had recently consumed a whole lot of plankton. The brightly colored nudibranch Cratena peregrina, with its luminescent blue tips, picked off the well-fed hydroids twice as often as those that hadn’t recently eaten (though no one’s sure how the sea slugs were able to tell the difference).

Researchers have given this newly observed behavior a name—"kleptopredation," a combination of "predation" and "kleptoparasitism," or the practice of stealing food from another species. Rather than simply taking the food from another predator, the sea slug is eating that predator as well as the prey it expended energy to catch. In short, that’s two meals for half the effort and a more diverse diet in the process. Sometimes crime really does pay.

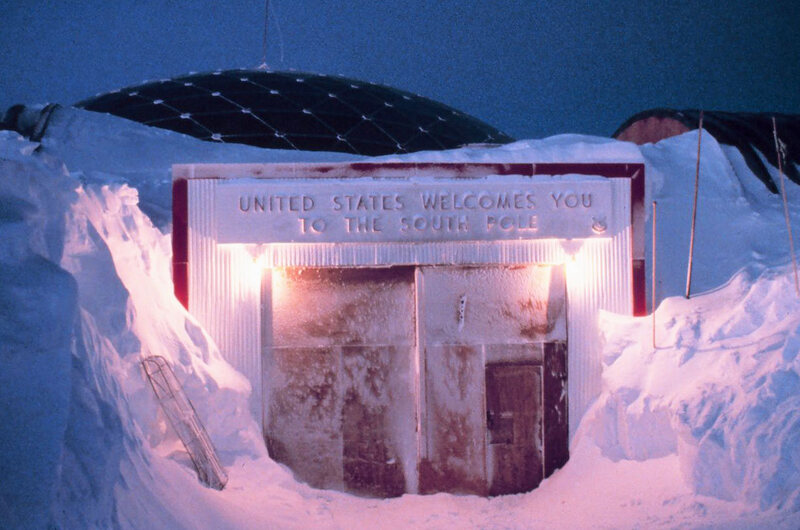

The Perils and Pleasures of Bartending in Antarctica

When Philip Broughton boarded a flight to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in 2002, he didn’t intend to become an Antarctic bartender. Following a terrible day at work, he had decided to get away, and, after a Google search and a two-year application process, he found himself on an American research station in Antarctica, working as a cryogenics and science technician for a year and a day.

A few weeks after his arrival in the summer of 2002, Broughton walked into the local watering hole, Club 90 South. “The only seat left was the one behind the bar,” Broughton says of his initiation into the pantheon of South Pole bartenders.

Broughton sat behind the bar and put his feet up against the beer case. Inevitably, someone asked for a beer. Glaring, Broughton handed one over. “Don’t get used to that,” he said.

But then someone asked if he knew how to mix anything. Which, thanks to a Playboy cocktail guide, he did. Using his own stash of Angostura bitters, he whipped up a Manhattan.

“And there I stayed for the rest of the year,” Broughton recalls.

Explorers have always packed booze. Ferdinand Magellan never sailed without wine and sherry. During the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Sir Ernest Shackleton stocked his ships with whisky to fight off the cold and endure voyages that could last more than three years.

Just as it was with Antarctica’s first visitors, so it is with its current residents. Every year, thousands of scientists, researchers, station staff, and even artists descend on Antarctica’s 45 research bases to live and work at the end of the world. (There are even more research stations if you include stations staffed only for the summer.) But those thousands winnow down to a persistent and hardy several hundred during the six nearly sunless winter months. (Once summer ends, planes and ships can rarely reach Antarctica due to storms and sub-zero temperatures that freeze fuel.) Their only external contact is through phones and the Internet. So the “winter-overs” come prepared … with heaps of alcohol.

Club 90 South was one of the many bars that serviced Antarctic research stations during Broughton’s winter on the continent. Broughton says that almost each of the 45 stations has a bar.

After stepping inside from temperatures that reached -100 degrees Fahrenheit, says Broughton, Club 90 South felt like a portal back to the real world. Constructed by the Navy “Seabees” Construction Crew out of building and shipping scraps, the cozy space had the warm, smoky atmosphere of harbor-side barrooms, with chairs, couches, and a classic wooden bar scattered around a low-ceiled room.

Over the bar, empty Crown Royal bags (the drink of choice at Club 90 South) hung from strings of Christmas lights like bulbous, satin ornaments. The freezer was a hole in the wall to the frigid snow and ice outside. Entertainment consisted of poker tournaments, watching TV, listening to music, reading left-behind books, talking with family and friends back home, and experiencing the station tradition of stripping naked (except for shoes) and running from the station sauna to the South Pole marker.

No one owned Club 90 South, and no one paid. Instead, people shared supplies they brought from home (as part of the allocated 125 pounds of luggage per person) or bought from the station store. Bartenders did not earn salaries—only kudos. Broughton started tending bar Fridays and Saturdays, and soon he spent most nights after dinner mixing cocktails and pouring a “disturbing number” of Prairie Fire shots, which Broughton made with tabasco and tequila. He served absinthes from the astrophysics team, Black Seal rum from a Bermudan at McMurdo Base, and Bundaberg rum from an Australian. Mixing his research job with his side hustle, Broughton made cocktails using liquid nitrogen, bringing the haute cuisine trend of molecular mixology to the bottom of the world.

The best (and worst) part? No official last call.

Club 90 South, with its homey, pool-room decor and casual atmosphere, became a lifeline for many barflys. In a place of near-eternal darkness that lacked restaurants and movie theaters, it doubled as a station “melting pot.” The bar “bridged the gap between the ‘beakers’ and ‘support,’” says Broughton, referring to researchers on National Science Foundation grants and contractors who operated and built the stations.

“A few months in, everyone in the bar knew everyone’s stories,” he adds.

But it wasn’t all cryogenic cocktails and sharing news from home. During the long months on a barren, isolated ice cap, drinking was often the only escape from the cold and monotony.

It’s an understandable reaction. Sink into a smooth glass of a favorite liqueur, and the cold bites a little less. The distance from loved ones feels more manageable. The time until the flight home, just a bit shorter. Some people drank to make the days go by faster. Regulars used pickaxes to clean frozen vomit off the ice outside Club 90 South.

Alcoholism can be a big issue in Antarctica. While there are no official statistics, some stations held Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and the hearsay was troubling enough that in 2015, the Office of the Inspector General audited several American stations. Due to reports of drunkenness on the job and alcohol-fueled fights, the National Science Foundation, which supports and operates U.S. scientific interests on the continent, is considering mandatory breathalyzer tests.

But Broughton says the honor system and communal atmosphere at Club 90 South helped prevent the affliction.

“It got people to drink together, rather than alone in their rooms,” says Broughton. “While you might drink more than normal with good company, that is still healthier than unchecked drinking alone, as good company might also slow you down.”

Broughton says he swapped out soda for booze when people drank too much, and he preferred to serve people so they could pass out in the bar, instead of watching them stumble out the door where, completely inebriated, they could hurt themselves or pass out in the snow.

After Broughton left the research station in 2003, Club 90 South closed during an effort to modernize Amundsen-Scott. But the legacy endures at other station bars, including Gallagher’s Pub, Southern Exposure, and the Tatty Flag. Broughton, meanwhile, is working as a radiation safety specialist at UC Berkeley, and he credits his time in Antarctica with his newfound interest in alcohol history and his appreciation for good, high-quality booze.

“I learned that if I’m going to consume alcohol, I’d better actually enjoy what I’m putting in my mouth,” he says. “Enjoyment is more than mere flavor.”

And would he go back?

“I would happily return for another winter” if my fiancée could come along, Broughton says. “I dream of Antarctica most every night. It is a haunting place.”

We’re launching a food section! Gastro Obscura will cover the world’s most wondrous food and drink. Sign up for our weekly email to get an early look.

The Modern Lives of Medieval Monster Scholars

There are certain subjects that, for many students, can be scary to talk about in the classroom. "If I were going to come in and say, ‘Today we are going to discuss religious discrimination,’ or ‘race relations in America,’ everyone would retreat into their corners," says Asa Mittman, a professor of art history at California State University, Chico.

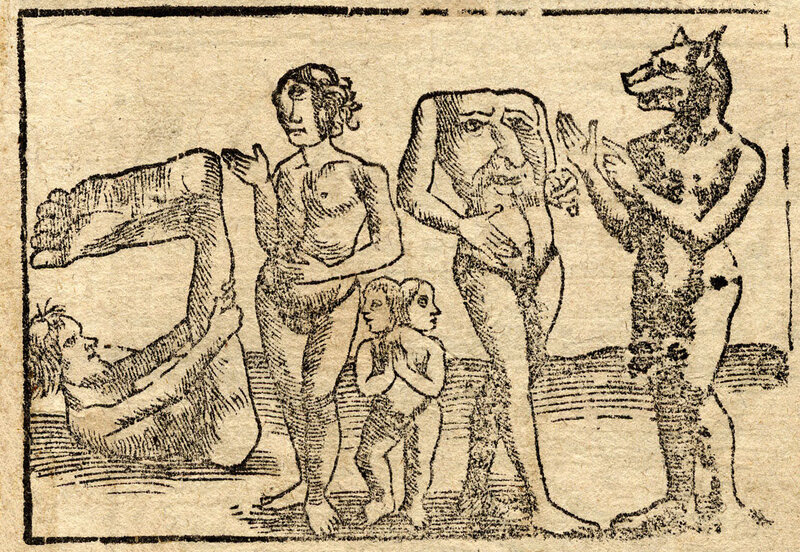

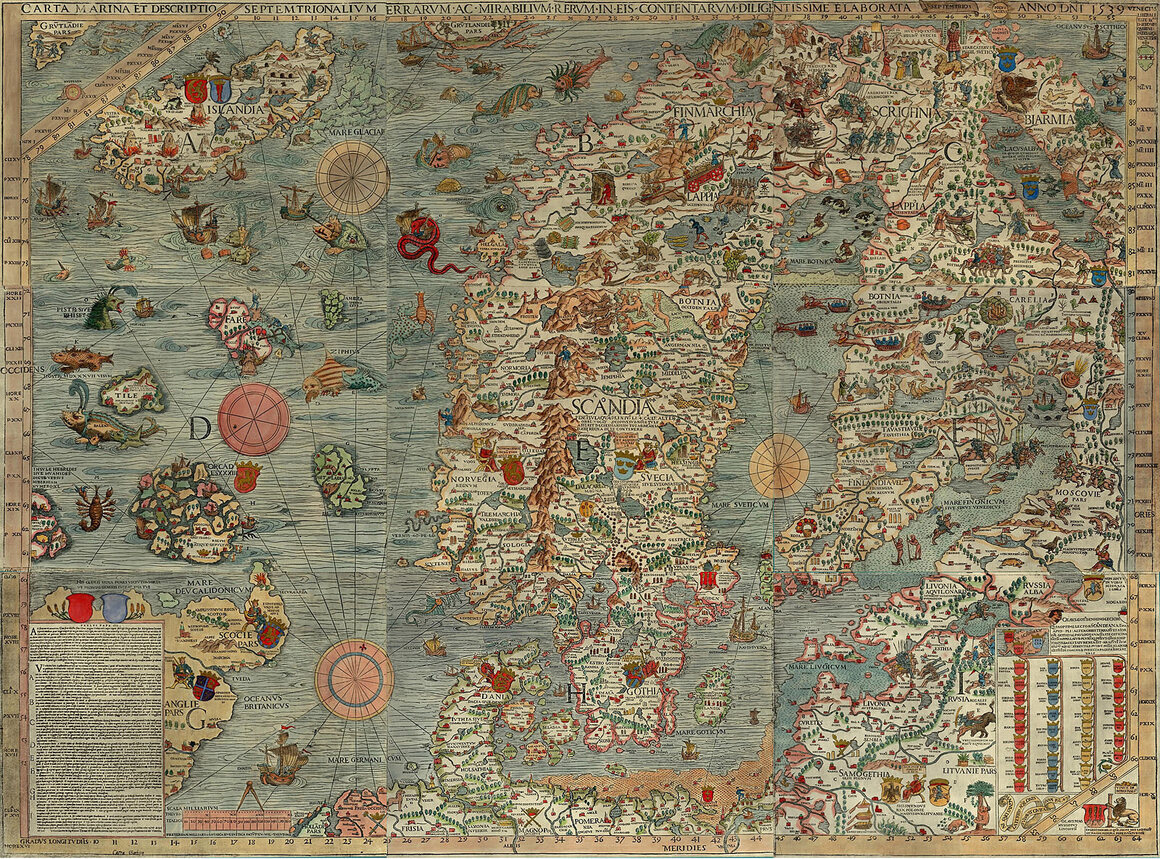

So if he does want his students grapple with such topics, Mittman might instead begin a discussion about blemmyes, a monster taken very seriously by medieval scholars. "A blemmye is a headless person who lives in the Red Sea," Mittman explains. "For scholars at the time, there were two important questions about blemmyes: Can they be converted to Christianity? And if they were, would they grow heads?"

Such are the problems considered by MEARCSTAPA, a group of scholars founded by Mittman in 2007. MEARCSTAPA, which stands for Monsters: the Experimental Association for the Research of Cryptozoology through Scholarly Theory And Practical Application, is committed to the study of medieval monsters—where they came from, what they can tell us about the people who dreamed them up, and increasingly, what lessons they might still offer today.

There are a few dozen active members of MEARCSTAPA. They collaborate on projects—panels about flaying and disguised demons; books about sea monsters and serial killers—and gather at medieval conferences. The group’s name is a purposefully ridiculous acronym, but it is also a word from Beowulf, coined to describe the monster Grendel, which translates to "border-walker" or "margin-stepper."

"It’s this great word that describes monsters writ large, as very many of them are at the edges of things," says Mittman.

MEARCSTAPA’s stated focus is the Middle Ages and early modern period, and most of the scholarship it has produced is focused on those eras. But "a lot of what we do is more relevant than it might seem," says Mittman, who defines monster scholarship as "the study of how individuals and groups—particularly powerful groups—dehumanize, disempower, and ultimately attempt to destroy other groups."

Thus the continuing relevance of, for example, blemmyes: a group of monsters whose change in religion, it was thought, might cause a change in physicality. If you follow this line of thought through to its conclusion, he says, "you wind up with perspectives about who is and who isn’t able to belong to a religion and who is and who isn’t a legitimate member of a nation—a citizen—based on race."

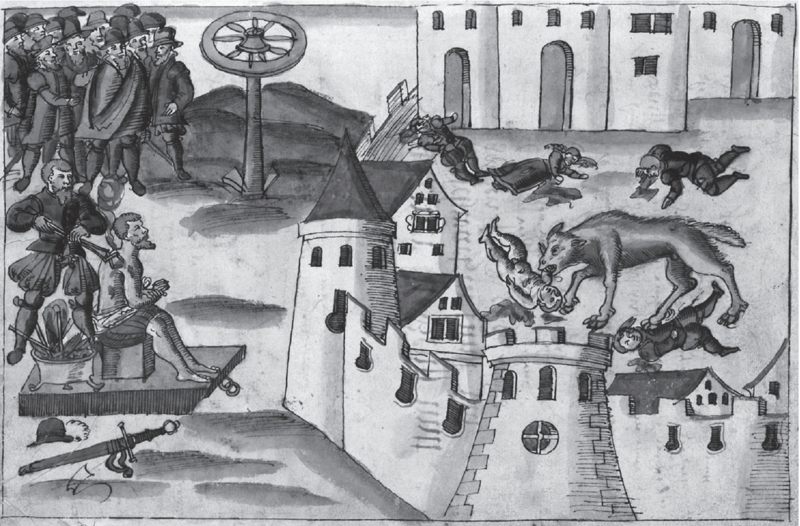

For MEARCSTAPA members, monster-hunting can often mean pinpointing what a group of people is afraid of, and looking for manifestations of it. "You get monsters that speak to the particular anxieties of cultural moments," says Mittman. For example, in the 1950s, as McCarthyism swept through the United States, horror movies focused on body-snatchers and other disguised extraterrestrials. The sexually repressive Victorian era gave us vampires, which remain anything but. For this reason, Mittman says, certain current crazes were eminently predictable to those in the know: "You say, ‘Oh, the economy’s going down,’" he says. "’We’re going to have zombies again.’"

Sometimes, monsters can be spotted in less obvious manifestations. Watching newscasters talk about this year’s hurricanes, Thea Tomaini—a professor of English at USC Dornsife, and a member of MEARCSTAPA’s executive board—was struck by how blatantly we demonize them. "They’re given names, they’re given personas," she says. "Every single time, you see the news outlets referring to them as monster storms."

This is also true, she says, of the larger problem of climate change. As people grapple with its causes, and try to figure out what can be done about it, Tomaini is reminded, she says, of a much older line of questioning: "Why has the monster come to us? Who has sent the monster, and why? What does the monster want?"

Problems can also arise when people disagree on who the real monsters are. Such confusion reminds Mittman of another beastly medieval staple: the false prophet, often depicted as a frightening, many-headed creature. Of course, to the people following him, he doesn’t look frightening at all. "It would be wonderful to have good, comforting monsters—the kind where you can look at it, see its fangs and horns, and have everyone agree, ‘oh, we should fight that,’" says Mittman. "But that’s not where we are."

Recently, MEARCSTAPA has been grappling with this particular type of monster close to home. As white supremacists have begun using medieval imagery to signal their devotion to an imaginary, racially homogenous past, the field has found itself divided over whether and how to condemn these associations. "Medieval studies is kind of on fire about this," says Mittman. "It has gotten people to show where they really stand on these issues, and that has sometimes been monstrous to see."

MEARCSTAPA sees this controversy as an opportunity to put their expertise to work, and they are hosting a session about it, called Monstrous Medievalism, at next year’s International Congress on Medieval Studies.

When MEARCSTAPA first formed, monster scholarship "was treated like a kooky endeavor," says Tomaini. "If you said ‘I work on monsters’ in a job interview, you might not get very far. But over the past ten years, interest in monster studies has really grown." Mittman agrees: "Now it’s a totally standard normal part of the field," he says. Two years ago, when he was on his way to a conference, a fellow scholar asked him about his focus. "I told her with much more confidence," he says. "And she sighs dramatically, and she says ‘Monsters! That’s all anybody works on!’"

Explaining their jobs to those outside the field is still difficult, though. "When I’m at a cocktail party, and I’m asked ‘What do you do?’, you should see people’s faces," says Tomaini. Monsters may change, but some things stay the same.

A Look Back at America’s Psychedelic Countercultural Witch Music

In the middle of the 20th century, pretty much anything went, in hip American circles, when it came to unlocking the doors of perception. A generation bent on questioning the social and moral status quo of the establishment was on an earnest quest for happiness, fulfillment and mind expansion. On this quest, a wide variety of tools and technologies were fair game for exploration—from alternative family and living structures (such as communal living or open marriage) to nonwestern belief systems and spiritual traditions, like the Zen Buddhism so beloved by the Beat poets. Searchers dabbled in psychedelics, astrology, yoga, Satanism, eccentric variations on Judeo-Christian faith, and psychology-driven groups, cults, and practices like EST and Scientology.

There was also magic. The surface aesthetics of witchcraft—long and flowing hair, beards and fabric, plus arcane symbols—dovetailed nicely with hippie fashion, and women-centered practice and a sense of connectedness to the earth and moon fit in well with new waves of female liberation and environmental consciousness.

The ‘60s counterculture wasn’t the first flowering of interest in magical practice or free love or Eastern spirituality in industrialized Western society. Waves had come and gone, most recently at the turn of the 20th century and in the 1920s creating recent lineages and legacies for the beatnik and hippie-era seekers to connect to. But one thing that was new, or new enough, was the utter explosion of the recorded-music industry and its overt alliance to the counterculture, and that is what we have to thank for a fascinating mini-trend of trippy recordings meant to open up the listener’s connection to the eternal power of the stars and her own innate magical ability to shape her destiny—and also sound very neat at cocktail parties.

Mainstream rock and rollers like Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones, of course, had dabbled in occult imagery and themes. Other recording artists had more direct connections to the dark arts: Graham Bond, a sax player and organist who played with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce before the other two musicians would go on to join Eric Clapton and become Cream, was to all accounts a practicing occultist in the Aleister Crowley mode, using a well-known quote (“Love is the Law”) from Crowley’s Book of the Law as an album title and recording under the name Holy Magick. Wilburn Burchette, who released seven albums in the ‘70s, regarded his psychedelia-meets-New Age guitar compositions as tools for mystical practice.

Vincent Price’s 1969 double album Witchcraft & Magic: Adventures in Demonology falls somewhere in between entertainment and instruction; bubbling cauldrons, whistling winds and other familiar chilling-and-thrilling sound effects underscore actresses quoting lines from Macbeth and his own signature over-the-top macabre theatricality. But he’s also quite deadpan in giving instructions for spellwork over creepy synth, and his tales of witchcraft in history, on tracks with titles like “Hitler and Witchcraft” and “Witch Tortures” if lurid, seem well-researched and accurate.

Louise Huebner, who released her Seduction Through Witchcraft album on the Warner Brothers label the same year, on the other hand, was definitely no actor. A psychic, palm reader and astrologer since childhood, Huebner had written several books on the occult and had a regular public presence in Los Angeles media, appearing frequently on radio and TV in her capacity as a practitioner of the esoteric arts. In her thirties when she recorded the album, she cut a rather elegant figure, with lush brunette waves and dramatically arched eyebrows adding to her glamorous, sexy hippie-witch look. When she received the formal designation of “Official Witch of Los Angeles County” at the Hollywood Bowl in 1968—a position that hadn’t been filled before, and hasn’t since—she cast a spell to increase the sexual vitality of her magical constituents. The spoken-word album, though it includes witch history and other general rituals described over electronic exotica, is, as the title implies, a sensual listen, with Huebner purring her way through the spells.

Seduction Through Witchcraft was reissued on vinyl in 2009. For Halloween 2017, a similar album (The Hour of the Witch) of recited spells from a Detroit-based witch named Gundella the Green Witch, originally released in 1971, got a similar treatment. It’s a beautifully done package, pressed on bright, antifreeze-green vinyl, and it includes a delightful booklet compiling examples from a column Gundella wrote—titled “Witch Watch”—for a regional newspaper chain in the ‘70s, in which, like an spookier, more prescriptive Dear Abby, she advised her readers on spells to assist in their particular predicaments.

The Hour of the Witch comprises several tracks of spell instruction (the “Spell to Make a Man Love You – Flower Bulb” is a notably little less than half as long as the “Spell to Make a Woman Love You – Wax Doll”) backed by subtle, mood-setting synthesizer music composed and performed by Gundella’s son. And that—very charmingly —is where its similarity to Seduction through Witchcraft, Adventures in Demonology or The Zodiac: Cosmic Sounds ends.

On tape, the accomplished sorceress Gundella, whose legal name was Marion Kuclo, sounds every inch the sensible Midwestern schoolteacher that she, having spent more than 20 years working in the Michigan public school system, was. The Hour of the Witch isn’t sexy, or dramatic, or space-age hip: it’s simply a no-nonsense guide to spellcasting, dictated in the sort of brisk, patient, authoritative voice one might also trust for advice on how to plant tulips, or breed spaniels. Giving directions on how to strain a potion, she suggests using cheesecloth, or “perhaps one of those new disposable coffee filters.” It’s easy to imagine her—maybe wearing the flowered muumuu she sports on the album cover—in front of the camera for the Food Network or a more eldritch version thereof, pleasantly shepherding novice magicians through a recipe. (“If you don’t have fresh eye of newt,” she might have said, “canned or frozen is fine.”)

Gundella’s daughter, Madilynne Mulleague, wrote liner notes to The Hour of the Witch, portraying her mother as the good-natured, friendly Michigan matriarch who comes across on the recording. She was a natural teacher, with boundless creativity and enthusiasm that benefited her grade-school students as well as her grown-up friends and acquaintances: she delighted in throwing theme parties, for which she would make piñatas, write original plays, and once, for a luau, built a six-foot-tall volcano—but she drew the line, Madilynne wrote, at serving alcohol. In 1992, the year before Gundella died from cancer, she published a book on Michigan-area hauntings, although she had long since given over her newspaper column from spellcraft to recipes and culinary advice.

It’s spookily ironic, then, that for all of her down-to-earth, demystified, cookbook-witch lifestyle, Gundella’s story is the one with the real-life horror for its coda. The famous witch had a second daughter, Veronica, who inherited her interest in magic and had opened a shop, Gundella’s Witchcraft and Wares, four years after her mother’s death, telling fortunes and selling tarot cards, spellbooks, and other occult items. Veronica was married to a man named Peter Raub, with whom she had four children. On Halloween morning 1999, the morning after the couple had hosted a Halloween party, Veronica Kuclo-Raub was found stabbed to death in the couple’s bed. “Man arrested in death of his witch wife,” read the Detroit News headline.

Mr. Raub, who had been charged with spousal abuse three years prior to the murder, was arrested in Los Angeles after a week-long manhunt. The children, three daughters and a son, went to stay with Ms. Mulleague, according to a mid-November report from the Detroit News—which also, in a surprisingly sensitive move for the time, ran a short piece examining its use of language in the coverage of Kuclo-Raub’s murder.

“In hindsight, we shouldn’t have said the slain woman was a witch in the headline,” wrote the News’ public editor. “Her religion was a critical part of her life, but not pertinent as it relates to the tragedy.”

Certainly, that’s the kind of sensible, thoughtful behavior that Gundella—the mom, the teacher, the advice columnist, the Green Witch—would have wanted to see.

Algorithmic Nature Puzzles – Nervous System’s ‘Geode Puzzles’ are Unique Like Natural Agate (TrendHunter.com)

(TrendHunter.com) While there are many nature puzzles on the market, Nervous System sets itself apart by producing the ‘Geode Puzzle,’ each of which is unique and created by a computer that makes…

Bell & Ross BR-X1 Skeleton Tourbillon Sapphire Watch

View Signal Source

Define Beauty: The Crown

Beer guts and tiaras scandalize the catwalk in Maxim Kelly’s playful film for our returning Define Beauty series. The dad-bod has gained a curious cultural status of late, embodying the celebration of ‘real’ masculinity. Kelly’s film throws a spotlight on these everyday bodies within the context of the most retrograde of events—the Miss Universe swimsuit competition. Here, the paunch takes center-stage.

The Crown questions the way in which ‘unmaintained’ male bodies—fed on a diet of beer, idleness, and pizza—are celebrated with a wink, rather than the judgment often reserved for maternal bodies.

"I was drawn to the idea of the dad-bod because I’m interested in subjects that have conflicting implications," says Kelly. "The dad-bod reinforces gender stereotypes, but it also turns the tables on them. It gives women a platform to speak in public about men in the way men have often talked about women."

The Best Comics & Graphic Novels of November 2017

4 Kids Walk Into A Bank, by Matthew Rosenberg, Tyler Boss, and Thomas Mauer This new book from up-and-coming publisher Black Mask is a part gritty crime heist story, part coming-of-age tale. Paige discovers that her father is about to be roped into pulling the proverbial “one last job” by […]

The post The Best Comics & Graphic Novels of November 2017 appeared first on The B&N Sci-Fi and Fantasy Blog.