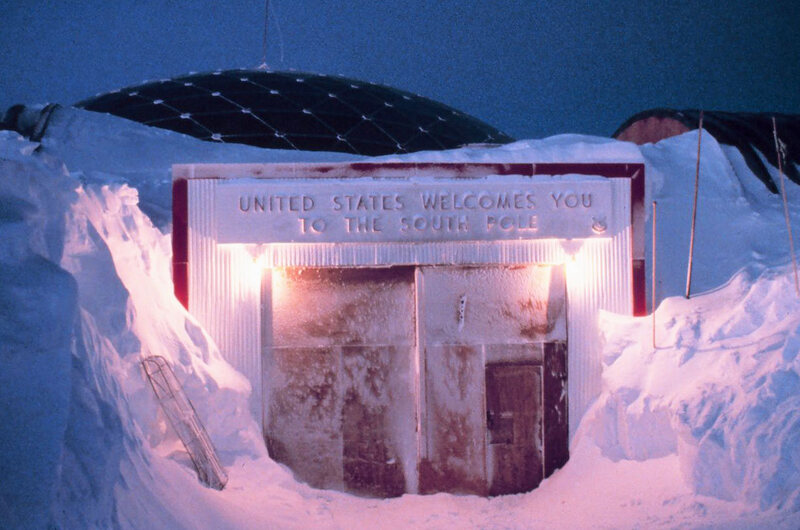

When Philip Broughton boarded a flight to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in 2002, he didn’t intend to become an Antarctic bartender. Following a terrible day at work, he had decided to get away, and, after a Google search and a two-year application process, he found himself on an American research station in Antarctica, working as a cryogenics and science technician for a year and a day.

A few weeks after his arrival in the summer of 2002, Broughton walked into the local watering hole, Club 90 South. “The only seat left was the one behind the bar,” Broughton says of his initiation into the pantheon of South Pole bartenders.

Broughton sat behind the bar and put his feet up against the beer case. Inevitably, someone asked for a beer. Glaring, Broughton handed one over. “Don’t get used to that,” he said.

But then someone asked if he knew how to mix anything. Which, thanks to a Playboy cocktail guide, he did. Using his own stash of Angostura bitters, he whipped up a Manhattan.

“And there I stayed for the rest of the year,” Broughton recalls.Explorers have always packed booze. Ferdinand Magellan never sailed without wine and sherry. During the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Sir Ernest Shackleton stocked his ships with whisky to fight off the cold and endure voyages that could last more than three years.

Just as it was with Antarctica’s first visitors, so it is with its current residents. Every year, thousands of scientists, researchers, station staff, and even artists descend on Antarctica’s 45 research bases to live and work at the end of the world. (There are even more research stations if you include stations staffed only for the summer.) But those thousands winnow down to a persistent and hardy several hundred during the six nearly sunless winter months. (Once summer ends, planes and ships can rarely reach Antarctica due to storms and sub-zero temperatures that freeze fuel.) Their only external contact is through phones and the Internet. So the “winter-overs” come prepared … with heaps of alcohol.

Club 90 South was one of the many bars that serviced Antarctic research stations during Broughton’s winter on the continent. Broughton says that almost each of the 45 stations has a bar.After stepping inside from temperatures that reached -100 degrees Fahrenheit, says Broughton, Club 90 South felt like a portal back to the real world. Constructed by the Navy “Seabees” Construction Crew out of building and shipping scraps, the cozy space had the warm, smoky atmosphere of harbor-side barrooms, with chairs, couches, and a classic wooden bar scattered around a low-ceiled room.

Over the bar, empty Crown Royal bags (the drink of choice at Club 90 South) hung from strings of Christmas lights like bulbous, satin ornaments. The freezer was a hole in the wall to the frigid snow and ice outside. Entertainment consisted of poker tournaments, watching TV, listening to music, reading left-behind books, talking with family and friends back home, and experiencing the station tradition of stripping naked (except for shoes) and running from the station sauna to the South Pole marker.No one owned Club 90 South, and no one paid. Instead, people shared supplies they brought from home (as part of the allocated 125 pounds of luggage per person) or bought from the station store. Bartenders did not earn salaries—only kudos. Broughton started tending bar Fridays and Saturdays, and soon he spent most nights after dinner mixing cocktails and pouring a “disturbing number” of Prairie Fire shots, which Broughton made with tabasco and tequila. He served absinthes from the astrophysics team, Black Seal rum from a Bermudan at McMurdo Base, and Bundaberg rum from an Australian. Mixing his research job with his side hustle, Broughton made cocktails using liquid nitrogen, bringing the haute cuisine trend of molecular mixology to the bottom of the world.

The best (and worst) part? No official last call.

Club 90 South, with its homey, pool-room decor and casual atmosphere, became a lifeline for many barflys. In a place of near-eternal darkness that lacked restaurants and movie theaters, it doubled as a station “melting pot.” The bar “bridged the gap between the ‘beakers’ and ‘support,’” says Broughton, referring to researchers on National Science Foundation grants and contractors who operated and built the stations.

“A few months in, everyone in the bar knew everyone’s stories,” he adds.But it wasn’t all cryogenic cocktails and sharing news from home. During the long months on a barren, isolated ice cap, drinking was often the only escape from the cold and monotony.

It’s an understandable reaction. Sink into a smooth glass of a favorite liqueur, and the cold bites a little less. The distance from loved ones feels more manageable. The time until the flight home, just a bit shorter. Some people drank to make the days go by faster. Regulars used pickaxes to clean frozen vomit off the ice outside Club 90 South.

Alcoholism can be a big issue in Antarctica. While there are no official statistics, some stations held Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and the hearsay was troubling enough that in 2015, the Office of the Inspector General audited several American stations. Due to reports of drunkenness on the job and alcohol-fueled fights, the National Science Foundation, which supports and operates U.S. scientific interests on the continent, is considering mandatory breathalyzer tests.

But Broughton says the honor system and communal atmosphere at Club 90 South helped prevent the affliction.

“It got people to drink together, rather than alone in their rooms,” says Broughton. “While you might drink more than normal with good company, that is still healthier than unchecked drinking alone, as good company might also slow you down.”Broughton says he swapped out soda for booze when people drank too much, and he preferred to serve people so they could pass out in the bar, instead of watching them stumble out the door where, completely inebriated, they could hurt themselves or pass out in the snow.

After Broughton left the research station in 2003, Club 90 South closed during an effort to modernize Amundsen-Scott. But the legacy endures at other station bars, including Gallagher’s Pub, Southern Exposure, and the Tatty Flag. Broughton, meanwhile, is working as a radiation safety specialist at UC Berkeley, and he credits his time in Antarctica with his newfound interest in alcohol history and his appreciation for good, high-quality booze.

“I learned that if I’m going to consume alcohol, I’d better actually enjoy what I’m putting in my mouth,” he says. “Enjoyment is more than mere flavor.”

And would he go back?

“I would happily return for another winter” if my fiancée could come along, Broughton says. “I dream of Antarctica most every night. It is a haunting place.”

We’re launching a food section! Gastro Obscura will cover the world’s most wondrous food and drink. Sign up for our weekly email to get an early look.